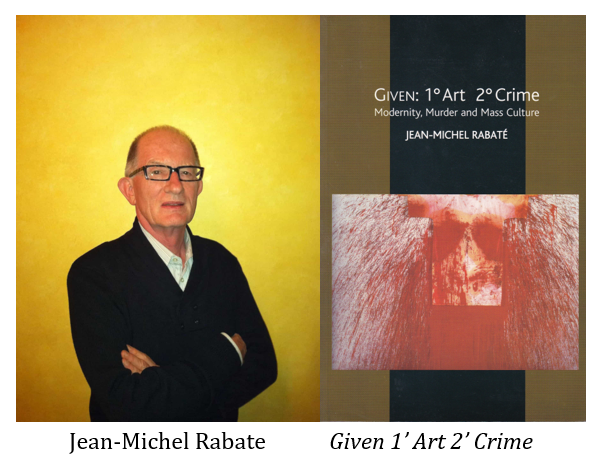

Author, Art Expert Jean-Michel Rabaté on Duchamp, Surrealism, and the Black Dahlia

September 6, 2025

Birch Bay, Washington

Jean-Michel Rabaté is one of the world’s leading voices on modernism and surrealism. A longtime professor at the University of Pennsylvania and author of more than forty books, he has shaped the fields of literary and cultural theory for decades. Rabaté is a founding curator of Philadelphia’s Slought Foundation, managing editor of the Journal of Modern Literature, and a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. His work spans Joyce, Beckett, Duchamp, and beyond—placing him at the center of conversations about how modern art and literature intersect with history and crime.

In 2007, Rabaté published Given: 1° Art – 2° Crime, his landmark study of Duchamp’s enigmatic final work Étant Donnés. In Chapter Two, he does something remarkable: he devotes serious attention to my Black Dahlia investigation. Rather than treating the case as just another unsolved Los Angeles murder, Rabaté frames it as an artistic and cultural event—deeply entangled with surrealism

“As Steve Hodel has shown in his meticulous investigation, the Black Dahlia murder cannot be separated from surrealist practice. The body was staged as an aesthetic event.”

Rabaté makes clear that he views the Dahlia case as solved and solved in the context of art history.

“Steve Hodel, who has successfully solved the mystery of Black Dahlia’s death, links this murder with one of the accomplices of the first murder, Fred Sexton. Hodel’s Solution to the Riddle … Steve Hodel pays homage to Ellroy’s novel in the memoir he has written — a memoir that shows with undeniable evidence that the main killer was his own father, the ‘genius’ George Hodel.”

“Étant Donnés presents us with a corpse that is also a spectacle, a tableau designed for the gaze. In this it echoes the shocking display left in a Los Angeles vacant lot in January 1947.”

Later in Chapter Two, he turns to Duchamp, underlining the disturbing resonance between art and crime.

“Here crime is given as art, and art is given as crime. The two converge.”

Rabaté’s analysis is divided into two halves: the first a detailed discussion of the Black Dahlia murder and my presentation of evidence identifying Dr. George Hill Hodel as the killer; the second a meditation on Duchamp’s “Étant Donnés”, with its unsettling tableau of a nude female corpse viewed through a voyeur’s peephole. These halves are not presented separately, but in dialogue. Rabaté recognizes the staging of Elizabeth Short’s body as a surrealist act that resonates uncannily with Duchamp’s last masterpiece.

In Rabaté’s reading, Duchamp and Hodel are not simply parallel figures but exist in a shared symbolic network. “Étant Donnés” becomes, in this light, less a private puzzle and more an echo of a public murder staged in Los Angeles in 1947.

Rabaté’s intervention matters because it places the Black Dahlia murder squarely within the discourse of twentieth-century art history. My investigation was never only about forensics and witness statements; it has always been about understanding how surrealist imagery, practice, and philosophy informed the staging of Elizabeth Short’s death. With Rabaté’s support, this case is seen not as a random act of violence, but as a chilling extension of surrealist thought into the realm of lived horror.

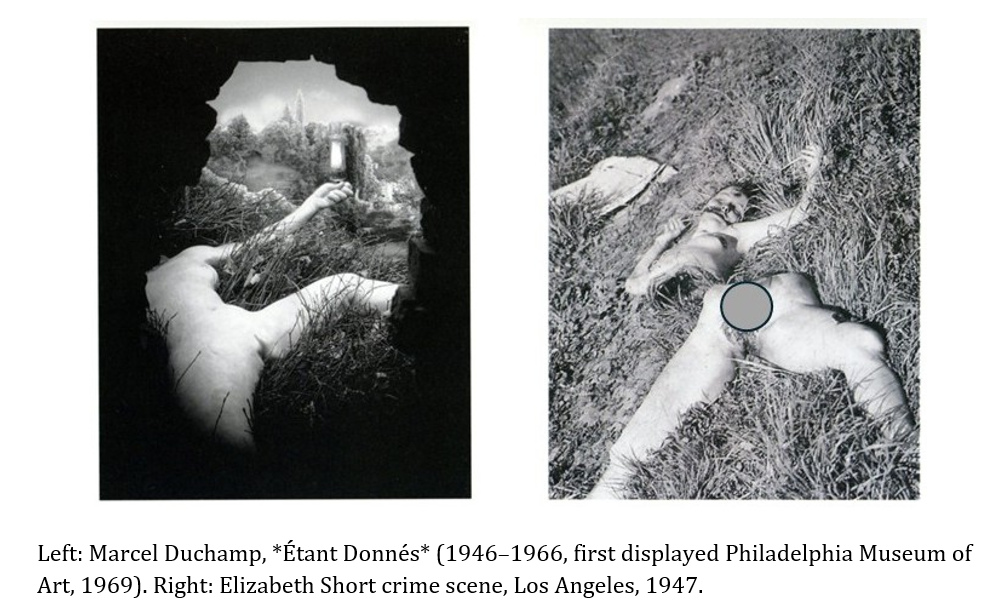

Duchamp’s Étant Donnés and the Black Dahlia Crime Scene:

A Disturbing Parallel

In examining the surrealist connections to the 1947 Black Dahlia murder, few comparisons are as striking—or as unsettling—as the one between Marcel Duchamp’s final masterwork Étant Donnés (1946–1966) and the crime scene photograph of Elizabeth Short.

In the above graphic, on the left, Duchamp’s tableau depicts a nude female figure, splayed in an open field, her body viewed through a darkened portal. On the right, we see the Los Angeles crime scene where Short’s body was deliberately positioned in the vacant lot on South Norton Avenue.

The similarities are undeniable:

Pose and Orientation: Both figures are displayed supine, legs spread in a ritualistic presentation.

Environment: Each lies on natural ground, surrounded by grass, weeds, and earthen texture.

Arm Placement: The left arm of each figure is bent upward, while the right arm extends outward, reinforcing a mirrored composition.

Voyeuristic Framing: Duchamp forces the viewer to peer through a “peephole,” echoing the public shock of Short’s body discovered in daylight, staged for maximum impact.

This juxtaposition is not coincidental. Duchamp began constructing Étant Donnés in 1946, the very year George Hill Hodel relocated to China, only months before Elizabeth Short’s murder. The overlap of surrealist imagery, criminal staging, and Hodel’s known connections to Man Ray, Duchamp, and the Los Angeles art world forms a sinister triangulation.

By censoring the more graphic detail in the crime scene photo, we can see more clearly the intentionality of the staging—not as random violence, but as an artistic and symbolic “installation” left for discovery.

As Rabaté concludes, in the Black Dahlia case crime became art, and art became crime — a convergence that still haunts both Los Angeles and modern art history.

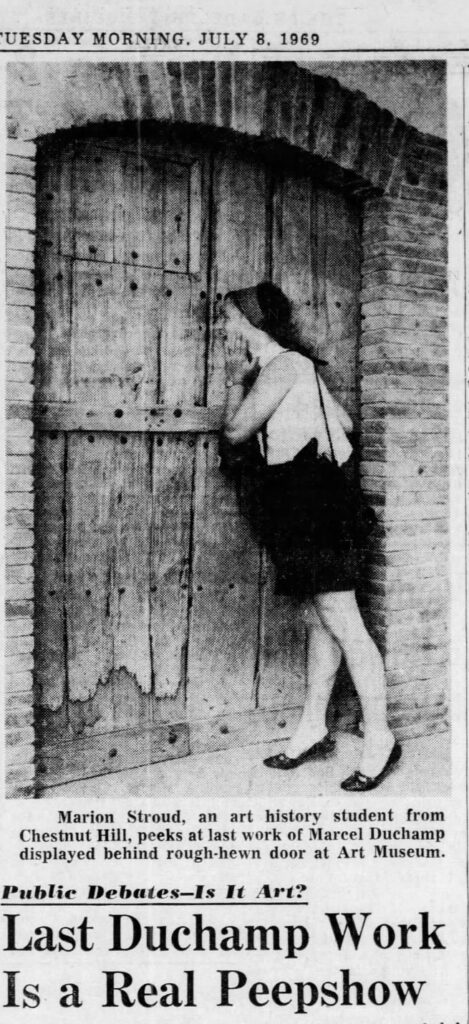

Original Etant Donnes Press Release article, July 8, 1969, Philadelphia Inquirer

This is a milestone for your decades-long investigation into the crimes of GHH. The fact that a noted academic has validated your work is significant in that it should elevate your work in the eyes of scholars from the often ridiculed genre of true crime books (let’s face it, many of them are full of factual errors and botched investigative techniques) to established history.

Perhaps some day instructors at police academies will use your books for teaching points on how to correctly investigate decades-old cold cases to get to the truth. Having read all but the last of your BDA books, I can say that your careful examination of facts and meticulous research into police files and newspapers is second to none.

Congratulations. I feel that your books will eventually become classics in true crime writing, if they are not already considered classics now.

Ron R:

Thanks Ron. Much appreciated. Thanks for taking a deep dive into all my books, which as you know, are really just one ongoing Homicide Follow-up report. Maybe one day I’ll really get brave and follow in the footsteps of those brave souls who tackle the myth that say’s that “William Shakespeare wrote all those plays way back when.” (I got a jumpstart on it when I bought Manly Palmer Hall’s “Big Book” some sixty-years ago.) Best to you and yours. Steve

Well deserved accolades. Validation. Academic validation, yes. However from my biased view, Professor Rabaté used your exhaustive investigation of the Black Dahlia Murder to validate, in fact and in part, his theories and speculations provided in his published work: “Given: 1° Art – 2° Crime” –not the other way around. Still a worthy call to a literary validation of time-delayed simultaneity.

(Given: 1° Art 2° Crime: Modernity, Murder and Mass Culture (Critical Inventions) Hardcover – September 1, 2006).

From the ‘About’ (Rabaté’s book) text on Amazon.com:

(Investigates links between avant-garde art and the aesthetics of crime in order to bridge the gap between high modernism and mass culture, as emblematised by tabloid reports of unsolved crimes. Throughout Jean-Michel Rabate is concerned with two key questions: what is it that we enjoy when we read murder stories? and what has modern art to say about murder? Indeed, Rabate compels us to consider whether art itself is a form of murder. The book begins with Marcel Duchamp’s fascination for trivia and found objects conjoined with his iconoclasm as an anti-artist. The visual parallels between the naked woman at the centre of his final work, ‘Étant donnés’, and a young woman who had been murdered in Los Angeles in January 1947, provides the specific point of departure. The text moves onward to Steven Hodel, the ‘Black Dahlia’ murder; Walter Benjamin’s description of Eugene Atget’s famous photographs of deserted Paris streets as presenting ‘the scene of the crime’; and Ralph Roff’s 1997 exhibition, which implied that modern art is indissociable from forensic gaze and a detective’s outlook, a view first advanced by Edgar Allan Poe.)

Robert S:

Thanks Robert. Much appreciated coming from a fellow retired police officer and crime wirtier with more than thirty five novels under his Dallas PD Sam Browne belt. https://www.robertjsadler.com/ Again, Happy Birthday partner.!

Wow – it’s simply incredible. Most murderers are straightforward and simple, even fi hard to solve. But GHH’s ES crime is way outside what was even imaginable to me until you spelled it out.