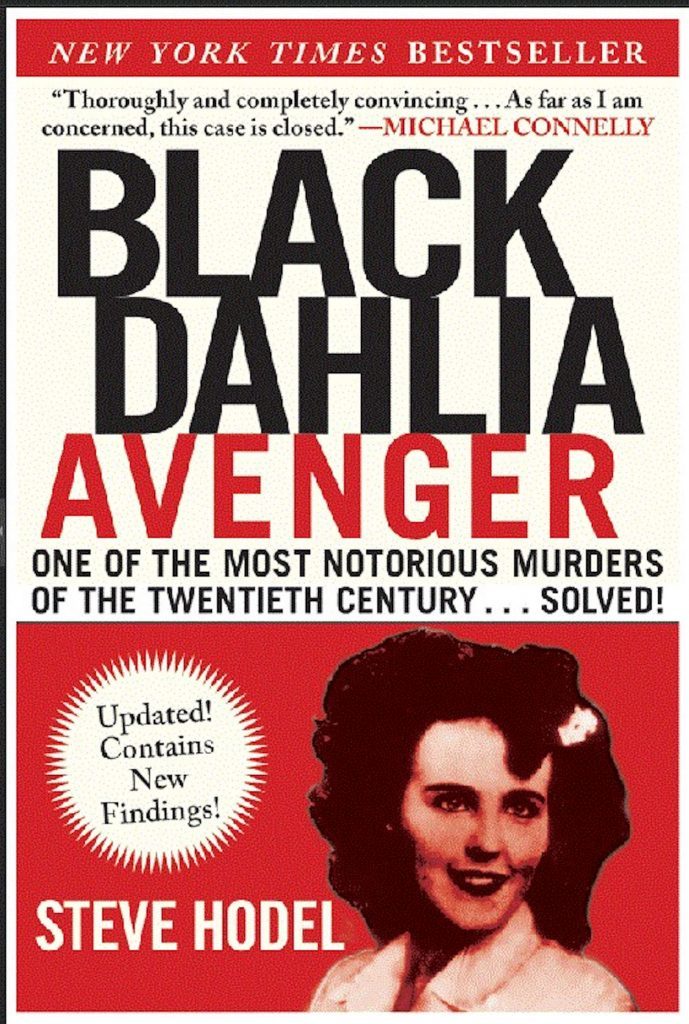

Black Dahlia Avenger

Buy the Book: Amazon, Barnes & Noble, IndieBound, Books-A-Million

Buy the Book: Amazon, Barnes & Noble, IndieBound, Books-A-MillionPublished by: Harper Paperbacks

Release Date: July 25, 2006

Pages: 624

Overview

In 1947, California’s infamous Black Dahlia murder inspired the largest manhunt in Los Angeles history. Despite an unprecedented allocation of money and manpower, police investigators failed to identify the psychopath responsible for the sadistic murder and mutilation of beautiful twenty-two-year old Elizabeth Short. Decades later, former LAPD homicide detective turned private investigator Steve Hodel launched his own investigation into the grisly unsolved crime—and it led him to a shockingly unexpected perpetrator: Hodel’s own father.

A spellbinding tour de force of true-crime writing, this newly revised edition includes never-before-published forensic evidence, photographs, and previously unreleased documents, definitively closing the case that has often been called “the most notorious unsolved murder of the twentieth century.”

To the above publisher-written overview, I will add what for me was a second and equally shocking discovery. The fact that the Black Dahlia Murder- was not a standalone crime. (Lost in time and perpetuated as myth was the fact that all Southern California law enforcement agencies: LAPD and LASD (police and sheriffs) and the DA’s investigators were aware and actively investigating at least five of the murders as probably being connected.)

I have dubbed, these —The Los Angeles Lone Woman Murders.

All of them committed by one man, my father, Dr. George Hill Hodel. How many? Difficult to say, however, I believe from 1943 to 1949, he committed somewhere between 7 and 20 serial murders in the Los Angeles and Southern California area. In BDA I break these suspected murders into separate “categories”. (Category I -Definites,--Category II –Probables and Category III -Possibles.)

In a letter, included in BDA’s original publication in 2003, one of the LADA’s most respected Head Deputy DA’s, Stephen Kay, confirmed that in his opinion, at least two of these murders (Elizabeth Short “Black Dahlia” and the Jeanne French “Red Lipstick”) “were solved.” Head DA Kay went further, indicating that if Dr. George Hill Hodel had still been alive, and had all the witnesses still been available, based on the evidence, he “was confident he could win the case in a jury trial.”

In May, 2003, post publication, Head DA Steve Kay and I briefed LAPD’s top brass and most agreed that the evidence was exceptionally strong and compelling. LAPD Chief of Detectives, James McMurray, present at the briefing also agreed with Prosecutor Kay that the Dahlia and Red Lipstick cases were solved.

Since 2003, (thanks to readers and witnesses coming forward both by letters and in emails) I have continued to build on the evidence which is chronologically summarized in my FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions) Section. Much of the information and evidence in these FAQs has been presented post-2006 and therefore cannot be found in the HarperCollins “revised” edition of BDA. (An updated FAQ INDEX by subject and FAQ section has been added. I.e., “Elizabeth Short – As Myth 7.1; George Hodel- as surgeon 17.2” See FAQ SECTION.

Praise

“The most haunting murder mystery in Los Angeles country during the 20th century has finally been solved in the 21st century.”

—Stephen R. Kay, L.A. County Head Deputy District Attorney“Los Angeles is the construct of its mythologies good and bad, fact and fiction. The legend of Elizabeth Short is one of the most enduring. Hodel's investigation is thoroughly and completely convincing. So too is this book. As far as I am concerned, this case is closed.”

—Michael Connelly, Bestselling author of The Lincoln Lawyer“We can only glimpse who Betty Short was—but now we know who killed her, and why.”

—James Ellroy, from his Foreword“Fascinating.”

—Johnny Depp

Excerpt

INTRODUCTION

For almost twenty-four years, from 1963 to 1986, I was a police officer and later a detective-supervisor, with the Los Angeles Police Department, a period generally considered to be LAPD’s “golden years.” I was one of Chief William H. Parker’s “new breed,” part of his “thin blue line.”

My first years were in uniformed patrol. My initial assignment was to West Los Angeles Division, where as a young and aggressive rookie, I was, as Chief Parker had demanded of all his men, “proactive,” excelling in making felony arrests by stopping “anything that moved” on the early-morning streets and alleys of Los Angeles. Over the next five years, as a street cop, I worked in three divisions: Wilshire, Van Nuys, and finally Hollywood.

In 1969, I applied for and was accepted into the detective bureau at Hollywood. I was assigned to and worked all of the “tables”: Juvenile, Auto Theft, Sex Crimes, Crimes against Persons, Burglary, and Robbery.

My rating within the detective bureau remained “upper ten,” and as the years flew by I was assigned to the more difficult and complex investigations, in charge of coordinating the various task force operations, which in some instances required the supervision and coordination of as many as seventy-five to one hundred field officers and plainclothes detectives in an effort to capture a particularly clever (or lucky) serial rapist or residential cat burglar working the Hollywood Hills.

Finally, I was selected to work what most detectives consider to be the elite table: Homicide. I did well on written exams and with my top ratings made detective I on the first exam ever given by LAPD in 1970. Several years later I was promoted to detective II, and finally, in 1983, I competed for and was promoted to detective III.

During my career I conducted thousands of criminal investigations and was personally assigned to over three hundred separate murders. My career solve rate on those homicides was exceptionally high. I was privileged to work with some of the best patrol officers and detectives that LAPD has ever known. We believed in the department and we believed in ourselves. “To Protect and to Serve” was not just a motto, it was our credo. We were Jack Webb’s “Sergeant Joe Friday” and Joseph Wambaugh’s “New Centurions” rolled into one. The blood that pumped through our veins was blue, and in those decades, those “golden years,” we believed in our heart of hearts that LAPD was what the nation and the world thought it to be: “proud, professional, incorruptible, and without question the finest police department in the world.”

2 BLACK DAHLIA AVENGER

I was a real-life hero, born out of the imagination of Hollywood. When I stepped out of my black-and-white, in uniform with gun drawn, as I cautiously approache3d the front of a bank on a robbery-in-progress call, the citizens saw me exactly as they knew me from television: tall, trim, and handsome, with spit-shined shoes and a gleaming badge over my left breast. There was no difference between me and my actor-cop counterpart on Jack Webb’s Dragnet or Adam-12. What they saw and what they believed—and what I believed in those early years—were one and the same. Fact and fiction morphed into “faction.” Neither I nor the citizenry could distinguish one from the other.

When I retired in July of 1986, then chief of police Daryl Gates noted in his letter to me of September 4:

Over twenty-three years with the Department is no small investment, Steve. However, twenty-three years of superb, loyal and diligent service is priceless. Please know that you have my personal thanks for all that you have done over the years, and for the many important investigations you directed. As I am reminded daily, the fine reputation that this Department enjoys throughout the world is based totally on the cumulative accomplishments of individuals like you.

During my years with LAPD, many high-profile crimes became legendary investigations within the department, and ultimately household names across the nation. Many of the men I worked with as partners, and some I trained as new detectives, went on to become part of world renowned cases: the Tate-La Bianca-Manson Family murders; the Robert Kennedy assassination; the Hillside Stranglers; the Skid Row Slasher; the Night Stalker; and, in recent years perhaps the most high-profile case of all, the O.J. Simpson murder trial.

Before these “modern” crimes, there were other Los Angeles murders that in their day were equally publicized. Many of them were Hollywood crimes connected with scandals involving early film studious, case such as the Fatty Arbuckle death investigation, the William Desmond Taylor murder, the Winnie Judd trunk murder, the Bugsy Siegel murder, and the “Red Light Bandit,” Caryl Chessman. But in those dust-covered crime annals and page-worn homicide books of the past, one crime stands out above all others. Los Angeles’s most notorious unsolved murder occurred well over half a century ago, in January 1947. The case was, and remains known as, the Black Dahlia.

As a rookie cop in the police academy, I had heard of this famous case. Later, as a fledgling detective, I learned that some of LAPD’s top cops had worked on it, including legendary detective Harry Hansen. After he retired, all the “big boys” at downtown Robbery-Homicide took over. Famed LAPD detectives such as Danny Galindo, Pierce Brooks, and old Badge Number 1, John “Jigsaw” St. John, took their “at-bats,” all to no avail. The Black Dahlia murder remained stubbornly unsolved.

Like most other detectives, I knew little about the facts of the case, already sixteen years cold when I joined the force. Unlike many other “unsolved,” where rumors flowed like rivers, the Black Dahlia always seemed surrounded by an aura of mystery, even for us on

INTRODUCTION 3

the inside. For some reason, whatever leads there may have been remained tightly locked and secure within the files. No leaks existed. Nothing was ever discussed.

In 1975, a made-for-television movie, entitled Who Is the Black Dahlia? and starring Efrem Zimbalist Jr. as Sergeant Harry Hansen and Lucie Arnaz as the “Dahlia,” was aired. It old the tragic story of a beautiful young woman who came to Hollywood during World War II to find fame and fortune. In 1947 she was abducted and murdered by a madman, her nude body cut in half and dumped in a vacant lot in a residential section, where a horrified neighbor discovered her and called the police. A statewide dragnet ensued, but her killer was never caught. This was all I and my fellow detectives knew about the crime. Fragments of a cold case, fictionalized in a TV movie.

On several occasions during my long tour of duty at Hollywood Homicide, I would answer the phone and someone would say, “I have information on a suspect in the Black Dahlia murder case.” Most of the callers were psychos, living in the past and caught up in the sensationalism of decades gone by. I would patiently refer them downtown to the Robbery-Homicide detail and advise them to report their information to the detective currently assigned to the case.

Despite the near-legendary status of the Black Dahlia, neither I nor any detective I knew ever spent much time discussing the case. It had not occurred on our watch. It belonged to the past; we belonged to the present and the future.

Law enforcement has learned a lot since the 1960s, when the first serious attempts were made to identify the phenomena known as serial killers. Earlier, with the exception of a few forward-thinking investigators scattered throughout the country, most case were characterized in the files of their local police departments as separate, unrelated homicides, especially if they happened to cross jurisdictional and territorial boundaries between city and county. For example, a murder on the north side of famed Sunset Boulevard would be handled by LAPD, but if the body had fallen ten feet to the south it would become the responsibility of the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department. As recently as the 1980s, these two departments rarely if ever shared information, modus operandi, or even notes on their unsolved homicides.

Today, experts in the fields of criminology and psychology are light-years ahead of their counterparts of even a decade ago in dealing with serial killers. Law enforcement officials have become much more aware and effective in their ability to connect serial crimes. Advances in education, training, communication, and technology, particularly in forensics and computerization, have made today’s criminal investigator much more aware of crime-scene potentials. He has “gone to school” on the Ted Bundys, Jeffrey Dahmers, and Kenneth Bianchis of the world. Through their independent analysis, joint studies and pooling of date, through interviews and observations, recognized experts in this highly specialized field have fine-tuned what we thought we knew, and have expanded on the old ideas.

Modus operandi, once recognized as only the most general of patterns, has now been broken down into specialized subgroups. Sexually sadistic murderers are categorized as “signature killers,” and that category in turn has several subtypes, depending on the specific act or acts of violence.

4 BLACK DAHLIA AVENGER

These experts have assigned new names to old passions that are crime-specific, and have attempted to identify individual psychotic behavior and link it to actions found at the scenes of multiple homicides. Connections are made by identifying conscious or unconscious actions performed by the killer. These actions are so specific that they reveal him or her to be the author, or “writer,” of the crimes. Hence the term “signature.”

Today, many more crimes are being connected and solved as police and sheriff’s departments across the nation open their doors and minds to the information and training made available.

That there exists a mental-physical connection to the commission of crimes is neither startling nor new. Every investigator is familiar with the old maxim of “MOM,” the three theoretical elements required to solve a murder case: motive, opportunity, and means. There are numerous exceptions to this rule, especially with today’s apparent alarming increase in acts of random violence, such as drive-by shootings. Nonetheless, motive remains an integral part of the crime of murder.

Most murders are not solved by brilliant deduction, a la Sherlock Holmes. The vast majority are solved by basic “gumshoeing,” walking the streets, knocking on doors, locating and interviewing witnesses, friends, and business associates of the victim. In most cases, one of these sources will come up with a piece of information that will point to a possible suspect with a potential motive: a jealous ex-lover, financial gain, revenge for a real or imagined wrong. There are as many motives for the crime of murder as there are thoughts to think them.

Our thoughts connect us to one another and to our actions. Our thought patterns determine what we do each day, each hour, each minute. While our actions may appear simple, routine, and automatic, they really are not. Behind and within each of our thoughts is an aim, an intent, a motive.

The motive within each thought is unique. In all of our actions each of us leaves behind traces of our self. Like our fingerprints, these traces are identifiable. I call them thoughtprints. They are the ridges, loops, and whorls of our mind. Like the individual “points” that a criminalist examines in a fingerprint, they mean little by themselves and remain meaningless, unconnected shapes in a jigsaw puzzle until they are pieced together to reveal a clear picture.

Most people have no reason to conceal their thoughtprints. We are, most if not all of the time, open and honest in our acts: our motives are clear, we have nothing to hide. There are other times, however, when we become covert, closeted in our actions: a secret love affair, a shady business deal, a hidden bank account, or the commission of a crime. If we are careful and clever in committing our crime, we may remember to wear gloves and not leave any fingerprints behind. But rarely are we clever enough to mask our motives, and we will almost certainly leave behind our thoughtprints. A collective of our motives, a paradigm constructed from our individual thoughts, these illusive prints construct the signature that will connect or link us to a specific time, place, crime or victim.

Solving Los Angeles’s most notorious homicide of the twentieth century, the murder of a young woman known to the world as the Black Dahlia, as well as the other sadistic murders discussed in this book, is the result of finding and piecing together hundreds of separate thoughtprints. Together with the traditional evidence, these thoughtprints make our case more than fifty years after the event, and establish beyond a reasonable doubt the identity of her killer, the man who called himself the “Black Dahlia Avenger.”